by Jim Havron (Independent Archival Consultant)

Archives and other heritage institutions vary greatly in size and resources. This may be obvious to those who read this, but it may not always be something that we think about when we attempt to preserve the historic record; whether that means digital or analog, Congressional papers or local history documents, physical or electronic, or whatever condition may apply. Likewise, IT staff quite likely does not understand the wide range of enterprise that may draw upon them or what resources are available. When we deal with cybersecurity, whether that means keeping hackers out or record integrity in, we will be dealing with IT. I would like to suggest some things that archivists might wish to consider.

Once again I repeat my basic premise, stated in previous posts:

It is the archivist who is responsible for the preservation and accessibility of electronic records under their care. When a donor places his/her records into an archivist’s custodianship, the donor expects the archivist to know how to keep them safe and make them accessible.

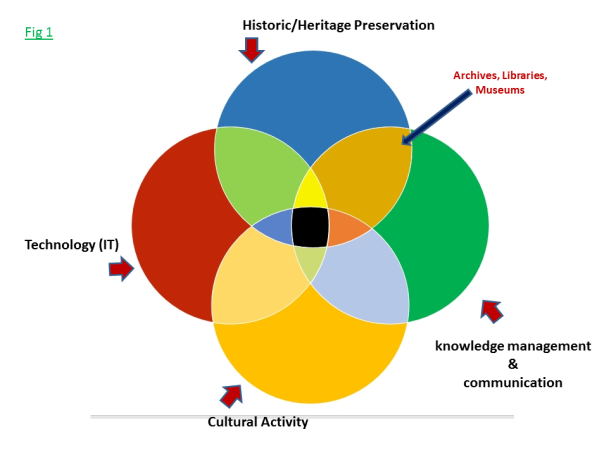

There are at least 4 general overlapping areas of concern for archivists dealing with electronic records. I will generally label them as historic/heritage preservation, knowledge management and communication, cultural activity (which can be business, government, art, etc.), and technology (particularly computer/cyber technology.) The accuracy of these particular labels at a given time or in a given situation is open for debate, but I think we can generally accept that something like them applies to our situation. (Fig 1)

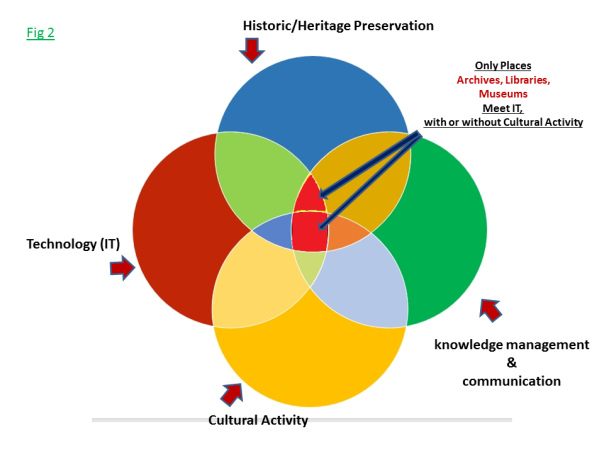

Archives, libraries, and museums fit in the preservation realm, and to varying degrees in the knowledge management/communication realm (The entire lens shape indicated by the arrow). They each have dealings with the actual activities that produce the records, publications, and communication (museums to perhaps a lesser extent) that is to be preserved, as well as the technology that is used to preserve it. The thing that must be remembered, as obvious as it may seem to the reader, is that there is a relatively small portion of the world of archives that intersects the world of technology. (Fig 2) The cyber world primarily deals with its own components and with areas of activity that are not directly connected with archives.

This may seem an involved way of explaining the relationships, but it is important because it explains that:

- Archivists and IT do not usually have the same goals

- Archivists and IT professionals do not speak the same language

- Archivists and IT professionals frequently cannot understand the needs, each of the other, in areas where they must work together

- The areas of activity where archivists and IT professionals must work together include cybersecurity and electronic records

If the majority of IT priorities and resources are focused on areas other than electronic records and cybersecurity in archives, archivists have serious difficulties assuring the preservation and access of the records under their care.

Add to this the following:

- Cyber technology is advancing much more rapidly than most organizations can afford to implement it. What is implemented is therefore done in a piecemeal fashion as resources allow or demand requires. Most large systems contain technology that was not designed to work together as a system. (This is actually true of most small systems as well.)

- With few exceptions, data and communication systems are designed to attempt to meet the statutory requirements for record longevity. Historical, long-term, enduring value, and permanent retention, are not concepts that are understood in IT, let alone part of its goals or priorities.

- Even when cybersecurity is a part of a system, most information technology is not designed specifically with security as a primary system goal

- Fewer than half of all enterprises have an up to date emergency preparedness/disaster recovery plan, and most such plans that do exist focus only on recovering data necessary to continue the primary function of the enterprise, not recovery of historical data

- While mobile devices have a part in (or are at least allowed) most enterprise technology systems, security for such devices is minimum at best. Almost none of the applications that do not come with the devices in their original state have undergone complete security testing. “Authorized” app store apps are not usually verified to be sure they have no malicious code or that known patches are in place. (Think about the number of apps that exist and picture the amount of time it would take to verify the code for each.)

- The vast majority of IT systems, at least one very experienced professional says close to 100%, have inherent weakness in security, efficiency, or even basic ability to function, are composed of components that are incompatible in some fashion. This is because they are not designed by a single project team working with components specifically designed to go together. From an IT point of view, additions and changes to a system that are requested by non-IT personnel are fraught with possible unintended consequences.

Ergo, IT has a lot to deal with providing a secure cyber environment, and often must do so without the proper training or resources, and often with little or no say in what components are added to a system.

Of course, IT folk generally have no understanding of what archivists need and want when dealing with electronic records. The fact that archivists are not usually working on the end of the record life cycle where records are created, let alone involved in the business and management decisions that lead to the activity that creates those records, often leaves us with a bit of uncertainty about what we need or want. We don’t generally see the metadata created in the day to day database governance. The term Internet of Things (IoT) is unusual to most of us, as well as the majority of IT, yet it vastly changed the flow and structure of information systems in the past couple of years. In short, we cannot expect IT to understand us any more than we understand the parameters under which they work. (Note: If you want to know more about the IoT, as with Big Data and “the Cloud”, take what you get from a Google search with a heavy grain of salt.)

When dealing with IT professionals, one must try to get some “buy-in” from them;

- Cultivate a relationship with a high-placed member of the department, developing a sponsor

- Know who your techs are, whether the people responsible for your server, your Webpage, backups, or desktop support. Let them know who you are and invite them to ask questions about what you do.

- Take an interest in any IT-related events, answer surveys, and learn about the IT environment

- Invite input when planning the storage and access of digital materials

- Acknowledge that IT generally has fewer resources needed to do the job expected of it (people seem to feel that computers can work magic at times) and accept that you may not be the top priority, but look for ways that you can take some of the load off so your project becomes “low-hanging fruit” and easier to take on.

- Bring donors into the conversation early so that the importance of the collection or project and the obstacles will be out in the open

- Once you develop “buy-in” from a high-level IT person, try very hard to stay in the loop as they change positions and responsibilities. Because of the demand for IT professionals, people change jobs frequently. I worked with an institution that listed an individual on their as the one in charge of servers, and found out that there had been four people in the position after he left.

Things to remember when planning your project or system:

- The network at the institution has likely evolved over a period of time, often in spurts that were not planned, and with multiple groups expecting different things from the network

- When something new is added to the network, it will affect more things than originally expected. IT networking is in the center of The Law of Unintended Consequences

- If you run your own network servers and are responsible for your own security, fine. Except that if your network joins another, work must be done by IT to integrate them.

We are all professionals, so we know how to deal with other professionals. At times, I think we tend to fail to understand what we really understand, and think we are being understood when we are not. We also fail to understand exactly what the other person’s job and training are.

The following are just a few examples of misunderstanding from my recent experience:

1) I spent almost my entire time at my last position trying to get university storage for high resolution video of television programs with members of Congress on them. Somebody from IT contacted at least once every 6 months to ask if I was finished with the storage. Sometimes whoever called stated they understood we were trying to keep these files permanently, but still wanted to know how soon they could be removed. (The head of one of the IT divisions is also an archivist. Knowing we were friends, someone went to him to ask why I wanted to keep electronic materials for so long. When the tech realized he just didn’t understand, he asked the division head “Is this one of those history things you guys do?” The head said yes and the tech gave up.)

2) I have discovered in some of the databases provided by Lockheed Martin some major mistakes in which the data was to be found in some dates. Constituent numbers entered as correspondence number, etc. Really rough stuff. I also figured out why the database indicated in multiple locations that there was correspondence in the database that was not there. It all had to do with changing systems during the tenure of the member of Congress. IT decided that this was useless data and wished to dump it. I decided that it showed us that correspondence had come in during that time, even if we did not have it, and that it showed where the technology changed in the office. IT could not understand why I would want to know that. A project archivist found even dirty data later on.

A relational database is designed to function in a special way. The data may have some meaning to some people if printed in a specific way, but when it functions in the work environment, it pulls data from different places to provide the information needed, and those places may not always be where one might expect. It performs calculations, logical queries, and sorts data. The data is not really stored in tables, only assembled that way for the viewer, and if a specific order is not needed and specified, it may arrange differently each time used. Think sort of 3-dimensional, 4-D if you include time. Functionality is an aspect of the database that must be preserved for the records to have meaning. I have had multiple archivists tell me that they just print the tables and save them as files. Think taking a picture of a tree and expecting that to represent the entire tree, through the change of seasons at that.

3) Data backup is a strange animal. The term is used generically to cover various forms of backup. In the entire time I held an archival position, I could not persuade my boss that the institution did not have a full, bit-to-bit copy of our 10T drive share somewhere. To IT, backing up the index was adequate, as it was the most likely part of the data to be damaged. If the server itself was taken out, well we were just out of luck. Maybe the boss was better off thinking otherwise.

Where is your data backed up? I have 5 data centers on major college campuses that had complete backups stored less than 200 yards from the primary center. Two are in tornado country, two are prone to flooding (one has the two centers literally sitting on the same river, just a few buildings away.)

At SAA 2015 in Cleveland, I was interested in a vendor who had backup systems that seemed to be affordable for medium-sized repositories, and possibly offer a backup solution for a small cluster of small archives to share. They could be used onsite or as a private cloud. I asked the vendor some questions as he stood there thumbing a stack of business cards he had collected for a prize drawing later. He asked what I did for a living and I told him I was an archivist. He told me that everyone who had submitted a card to his “fishbowl” for the drawing had been required to hand it to him so he could ask them how they kept their data secure, whether electronic records, scanned images, or personal records. He had 72 cards in his hand. He told me I was not only the first person to ask him multiple questions about his products, but that everyone else who answered said they just gave what they got to IT and let them worry about it. This was his first and, he planned, last visit to SAA.

Things to think about!

Note: Most of the specific source material in this post came from personal experience, seminars, and conversations with IT professionals. ISACA and SANS websites have some access to similar materials.